The Winter's Tale

This play is considered to have been written sometime between 1594 and 1608, and is categorized as one of Shakespeare's five Romances (The Winter's Tale, Cymbeline, Pericles, The Tempest, and Two Nobel Kinsmen)

Shakespeare's plays are commonly categorized into four sections: Comedy, Tragedy, History, and Romance. Romance confusingly seems as if it should simply be usurped into the name of comedy, but Shakespeare's romances present a complexity which cannot be bound by the conventions of comedy.

Romance refers to the types of fictions that were being written during the Renaissance, such as Sir Philip Sidney's "The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia" (c. 1588) and Lady Mary Wroth's "The Countess of Montgomery's Urania" (c. 1621). Following the tradition of Hellenistic literature, these fictions are very extensive with multiple story-lines, dozens of characters, and endless (sometimes repetative) plots. As Professor Black said in a seminar, "in Romances there can always be another dragon". Romance "novels" (technically the first novel wasn't written until the times of Defoe in the late 17th century) are circular and do not need a place to end, thus they feed back on themselves and continue the tale.

Plays that are referred to as Romances often have these distinctive features:

*They span over a great period of time and place. (Most of the comedies occur within a short time frame, days to weeks, and usually within the same city, or at most three cities.) Shakespeare's Romances span over years and lifetimes.

*A moral, redeeming ending (not as cryptic as his comedies or as dire as his tragedies)

*The reuniting of long-lost family members (although his plays such as "Comedy of Errors" and "Twelfth Night" have this plot device, these reunions are not the zenith but rather the confusion of lost characters provides the humor, whereas in Romances the separation causes the conflict and the finding the solution)

*The presence of pre-Christian, mythological characters, sometimes acting as the Deux Ex Machina (where in the comedies and tragedies this divine role is usually bestowed on a human being, such as a Prince or a King.)

*The use of magical elements (although I disagree with this classification because we see magic throughout "A Midsummer Night's Dream", "Macbeth", "Othello", and "Richard III".)

*And the combination of pastoral and court scenes.

| I picture the Renaissance Romance as being similar to a snake biting its tail.

And to go along with biting tails, I think the beginning of the story of a romance links with the end, snatching its own tale. (Oh yes, I did make a weak pun).... in short the Arcadia and Urania can seem endless in their circular plots (not adhering to plot-lines but rather plot-circles) |

The Winter's Tale

Act I. Scene i.

An Antechamber in Leontes' Palace

Enter Camillo (servant to King Leontes of Sicila) and Archidamus (servant to King Polinexus of Bohemia)

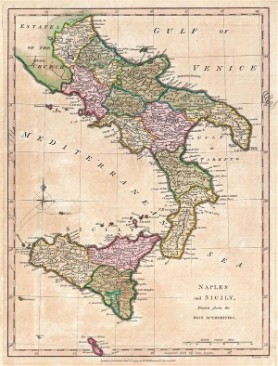

The setting of the first half of The Winter's Tale is in Sicilia, which is located in the Mediterranean Sea (an excellent place for trading power-- Sicilia's fertile soil made it a leader in the markets of olive trees and grape vines) and is just at the tip of the boot of Italy. Sicilia (also known as Sicily) was colonized by the Greeks in about 750 BCE and is studded with many jewels of the ancient era, such as the Necropolis of Pantalica (a cluster of over 5000 tombs dating between the 13th and the 9th centuries BCE) and the Temple of Hera at Selinunte. The time period of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale is set during the Greek rule because much of the religion is pagan, and Leontes even requests an oracle as a witness against his wife-- thus we can assume the play is set during the Greek dominance, between 750 BCE and the Roman annexing around 242 BCE when Sicily became part of the Italian Peninsula following the First Punic War. The country went through many changing of hands, from being sacked by the Germanic Vandals in 440 AD, to being overthrown by the Byzantine Empire in the 6th century AD, and then succumbing to Norman Invaders in the 12th Century AD-- and in the 1860's Sicilia became part of Italy under the unification initiative lead by Guisseppe Garibaldi, although Italy and Sicily and markedly different and they should always be acknowledged as such. | Shakespeare's plays usually begin with secondary or tertiary characters who introduce situation and supply background information. From this brief speech we learn that Archidamus is in Sicilia on business matters (matters of state as he is servant to a King). He expresses a hope that Camillo will be able to go to Bohemia, also on business, and see the difference between the two nations. [The difference in nations also implies the difference between the King's-- aka the heads of states.]  |

Leontes, King of Sicily, plans to visit Bohemia the approaching summer. The mention of "coming summer" implies that the beginning of this play is occurring during the winter. (Hence one of the reasons for the play's title) |

In humble policy, Archidamus says that although Bohemia may not prove as entertaining (rich and performative) as Sicilia, they will make up for their lack of flare with their sincerity and affection by which they tried to entertain-- the idea being, "it is the thought that counts". Camillo, in polite retort, offers to stop Archidamus from belittling his country and what it has to offer. (I imagine this genteel exchange of being something like when I invite my mother to my apartment after spending all day cleaning and bashfully saying, "sorry, mom, I didn't really have time to clean.") |

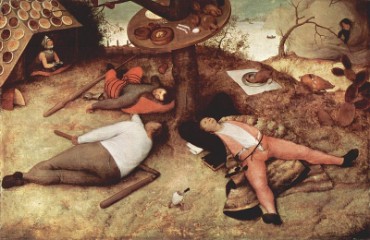

| Archidamus will not be stopped in his speech, but tells Camillo that he only speaks what he knows, and that is Bohemia cannot supply such wonder to their guests. But then he halts, drifting his words into "I know know what to say", which negates his earlier line about how he only gives voice to what he is familiar. This stopping and starting and calculated self-doubt are tropes of flatters (as seen more maliciously in Shakespeare's Iago.) Archidamus continues that they will give their guests "sleepy drinks"-- probably a port wine-- which will make them so drunk that they will be unaware of Bohemia's deficiencies, which may mean they will not be able to praise Bohemia's successes but, more importantly, not be able to criticize the country of lacking pleasures. To the left is the painting "The Land of Cockaigne" by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The men lie drunk on the ground after satisfying their gluttony on food and wine. Helpless but happily inert this is the vision which Archidamus paints of how the guests will be indulged into satiated reticence by wine. This piece was completed in 1567. Cockaigne is a fabled land of plenty. |

CAMILLO: You pay a great deal too dear for what's given freely. | Camillo counters the self-deprecation by implying that Sicily loves Bohemia, and is paying a large deal of flattery and offered hospitality for respect and enjoyment that Bohemia is already feeling and will undoubtedly feel upon visitation. |

He again refers to only speaking what he knows to be true and it is his inclination toward truth that invokes him to speak. (For there can be no truth if it is not spoken-- much like if there is no witness then no declaration of truth can technically be made). Archidamus is the witness to the truth of his own comprehension. |

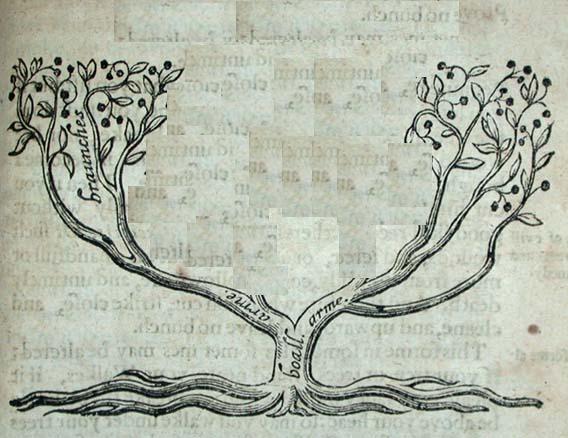

CAMILLO: Sicilia cannot show himself over-kind to Bohemia. They were trained together in their childhoods; and there rooted betwixt them then such an affection, which cannot choose but branch now. Since their more mature dignities and royal necessities made separation of their society, their encounters, though not personal, have been royally attorneyed with interchange of gifts, letters, loving embassies; that they have seemed to be together, though absent, shook hands, as over a vast, and embraced, as it were, from the ends of opposed winds. The heavens continue their loves!  This edited drawing of a tree represents the branching of Leontes and Polixenes. The roots like their infancy before meeting are separated in a similar fashion as the branches, but the trunk is the union of their education and childhood, which they later branch from during their respective reigns. | The names of the countries now represent their kings: Sicilia is Leontes Bohemia is Polixenes The two rulers have known one another since they were boys and were "trained together"-- training here means in war as well as the arts and sciences. It is not acknowledged where the two young princes could have cohabited, although I do think the circular option typical of a romance would be in Bohemia, for that is where their own children meet a fall in love in the second half of the play. Although they may have been sent to be educated out of both of their homelands, similar to Hamlet being school in the foreign city of Wittenberg. The place of their education is likened to soil from which the two princes grew in the form of one tree, but as time and duty demanded, they had no choice but to branch and both princes went in different directions but still stayed rooted to their early dedication to one another. The imagery here is the same as when Helena bewails to Lysander and Demetrius in "A Midsummer Night's Dream" that she and Hermia "grew together, like to a double cherry seeming parted,/ but yet an union in partition;/ two lovely berries moulded on one stem;/ So, with two seeming bodies, but one heart" (III.ii). Over the years the kings have maintained a fast friendship and even though they were not able to be together physically they kept up communication by sending messages and gifts. Polixenes and Leontes were able to succeed in a long distance relationship during which they never lost contact but were able to embrace by means of their frequent and present-laden communications. The words "attorneyed", "royal necessities", and "interchange" imply a diplomatic affiliation that accompanies their personal friendship, proving their business and personal lives can harmoniously mix. A vast refers to the body of water which separates Sicily and Bohemia (however, Bohemia does not in reality have a coast, yet in this play Bohemia is fixed at the cusp of a sea.) And the "ends of opposed winds" illustrates the two countries as ships, blown in different directions (a slightly similar idea as the branched tree of their friendship and duty). The ending of the speech, "the heavens continue their loves!" is a kiss of death for the relationship. Shakespeare cannot let a well wish be carried out but must curse it with the opposite of what is requested. |

The Camillo referenced elder who, already on crutches, wishes his life to be extended to see Mamillius become king. This piece is a silverpoint etching on a prepared tablet entitled "A Beggar on Crutches Walking to the Left" by Andries Both. It is undated, but the artists' life span from 1612/13 to 1641. | Adding to the curse of well-wishing, Archidamus adds that he believes there is no humanly contrived evil or surcumstance to change Polixnese's and Leontes' love. He then turns to the subject of Leontes' son, Mamillius, who is noted as being an "unspeakable comfort". Princes were always considered to be a form of safety for a nation for it ensured there would be a king. Although this play was written during the lifetime or a few years after the reign of the most notorious of queens, it was still believed princes meant a solidity of crown. Lines of succession were a source of much anxiety in royal families and so a legitimate son meant the difference between the familiar and the unknown. Any heir to a throne, whether male or female, is a much greater comfort than none at all, but a boy is often preferable. Mamillius is further noted as being an excellent "gentleman" who shows himself to have potential for being a great king. So not only is the heir a boy, but the addition of his "great promise" is an even more swaddling assurance. Side Note: What's In a Name: Mamillius The root of the word Mamillius comes from the Latin Mamilla meaning breast or teat. It is the same root from which we get the words mammary, mammogram, and mamma. (Mamma, a common nickname for a mother, thus comes from the terminology associated with her breastfeeding). Mamillius' name thus givens him a close connection with the feminine, most notably the maternal. His association with females becomes more evident in a later scene. The child's death occurs because of his denied access to him mother-- and although he is well past the age of nursing (he is probably between the ages of 5 and 7) his seclusion from the metaphorical breast could be recognized as the cause of his demise (along with the execution of the divine prophesy of the oracle). An interesting note is that Hermione would not have breastfeed her son as during the Renaissance it was believed to be a low task and a wet nurse was chosen to nourish the strange child with her own bosom. Hermione assuredly did not nurse Mamillius for Leontes later serves her with the insult "I am glad you did not nurse him" in Act II. |

Camillo shares the same expectation that Mamillius will grow into a great king, for he is a noble and brave child. He goes beyond his own opinion and extols the boy by saying the citizens of Sicily also believe he will be a great ruler. Camillo singles out the older denizens saying that even though old enough to be on crutches when the prince was born (a stereotypical visual of age is of a person on crutches) they prayed to live long enough to see the boy age into the great king that the root of the child promises. |

ARCHIDAMUS: Would they else be content to die? CAMILLO: Yes; if there were no other excuse why they should desire to live. ARCHIDAMUS: If the king had no son, they would desire to live on crutches till he had one. | The Bohemian courtier questions whether these citizens would have any other reason to live for and Camillo responds candidly and in a cheeky manner that if the people had any other reason to live they would. This line implies that the elderly wanting their lives prolonged is not exclusive to seeing Mamillius become a man but rather they would want to live in general. The quip belittles the importance of royalty in the private existence of commoners for it is not a future king that makes them hold on but rather just having anything to hold on for. Archidamus casts a gloomy shadow of foreboding that if Mamillius never existed or died the people would stay alive in hopes of seeing a new heir. The inability of people to die until their is a new king is a metaphor for the inability to find rest and peace until a royal succession is insured. |

Act I. Scene ii

Another Room in the Same State

Enter Leontes (King of Silicia), Hermione (his wife and Queen of Sicilia), Mamillius (their son and the prince), Polixnese (King of Bohemia), Camillo (his courtier), and attendants

POLIXENES: Nine changes of the watery star hath been The shepherd's note since we have left our throne Without a burthen: time as long again Would be find up, my brother, with our thanks; And yet we should, for perpetuity, Go hence in debt: and therefore, like a cipher, Yet standing in rich place, I multiply With one ' We thank you' many thousands moe  Illustration of a trajectory of a solar eclipse composed by British astronomer Thomas Hewit in 1654. | The "watery star" is a reference to the moon. Astronomically the moon has many associations with water, the most scientifically relevant of which is its control over the tides; and the moon also has astrological associations with water. The planetary body is located under the sign of Cancer and the emblem of this sign is the crab which is a sea-dwelling creature. The moon during the Renaissance was also understood to be the opposite of the sun, and naturally the sun is associated with fire, thus his counterpart would be a watery moon. Solar eclipses when the moon passed over the face of the sun were also believed to be caused by the quenching power of water-- for as liquid extinguishes flame so did people believe the same held true for the planetary bodies. The moon has changed nine times during the course of Polixenes' stay which indicates he has been in Sicily for 9 months. Currently, a full lunar cycle occurs every 29.53095 days which includes the eight phase changes within each cycle ( new moon, waxing crescent, first quarter, waxing gibbous, full moon, waning crescent, last quarter, waning gibbous)-- the trajectory of this 29 day period being the time is takes for the moon to orbit the earth. The statement that Polixenes has been in Sicily for 9 months will be used later in the case again Hermione as proof of infidelity, because Leontes accuses her of becoming pregnant upon Polixenes' arrival. The "shepherd's note" is simply that the shepherds in Polixenes' homeland of Bohemia (which we will later find a comedic pastoral land) have marked the 9 months since Polixenes and his courtiers departed. Polixenes claims that it would take another nine months "time as long again" to properly thank Leontes. The idea being that Polixenes would spend the entire time repeating the words "thank you". In filial bond, Polixenes calls Leontes his "brother". Despite this prostrating offering of thanks, Polixenes recommends for "perpetuity", endless eternity, they must leave without paying the full amount of auditory appreciation and consequently depart "in debt". Polixenes is positing there is no time to give all the thanks their stay deserves. (Like their servants, Camillo and Archidamus, Polinexes and Leontes are great flatterers and applauders of hospitality. The Bohemian king concludes that "like a cipher"-- a person of no influence or value-- yet rich when he is in Silicia, must embody a thousand "thank yous" in a solitary thanks. |

LEONTES: Stay your thanks awhile and play them when you part POLIXENES: Sir, that's to-morrow. I am question'd by my fears, of what may chance Or breed upon our abscence; that may blow No sneaping winds at home, to make us say 'This is put forth too truly.' Besides, I have stay'd To tire your royalty. LEONTES: We are tougher, brother, than you put us to't. POLIXENES: No longer stay. LEONTES: One seven night longer. POLIXENES: Very sooth, to-morrow LEONTES: We'll part the time between's then; and in that I'll no gainsaying. | In the above speech, Polixenes did not say he was decided upon leaving so Leontes may have recognized his words as just an opulent passing thank you. King Leontes assures Polixenes that there is no need to say his thank yous for he is not leaving yet. Polixenes puts a date on his departing. As per typical foreshadowing, Polixenes says he is haunted by a worry something bad will germinate during their absence from one another. He hopes there are "no sneaping winds at home" which will prove this ill premonition true. -- To sneap is to rebuke or reprimand, and here might mean he wishes there to be no reason for the two kings to hate one another or for their people to hate them. -- The winds here referred to mirror those spoken of by Camillio in scene one, with the Kings being at "ends of opposed winds". Both these winds are respective to their homelands which is where their duty resides and their homes are the reason for their long separations. The King of Bohemia then snaps out of his foreshadowing and comes to the reality that they have relied upon Leontes' hospitality too long and their residence at the palace is becoming long-stayed and burdensome. While maintaining the goal of retaining Polixenes, Leontes boasts his resiliance and strength which will be shown later in the brutality of his trials, although he is reduced to a broken, shameful man after. Polixenes puts flattery aside and drives straight into the point: that he must go. "One week more" "Truly, I must leave tomorrow." |